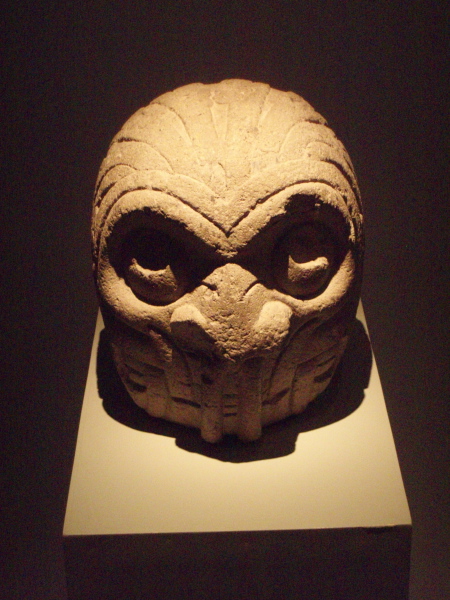

While the stone sculpture is what stands out about the Chavin, they also produced some fantastic early examples of ceramic art, rivaling the roughly contemorary Cupinisque style of the coast. An example of the former is the huge condor head to the right; several ceramics are shown below, including a shocking depiction of a man whose throat has been cut, several forms imitating vegetables, and a bowl depicting the three-step andean image which became ubiquitous in Inca religious art.

While the stone sculpture is what stands out about the Chavin, they also produced some fantastic early examples of ceramic art, rivaling the roughly contemorary Cupinisque style of the coast. An example of the former is the huge condor head to the right; several ceramics are shown below, including a shocking depiction of a man whose throat has been cut, several forms imitating vegetables, and a bowl depicting the three-step andean image which became ubiquitous in Inca religious art.

Chavin de Huantar

The heart of the Chavin culture is the ceremonial center of Chavin de Huantar, a granite temple located in the northern mountains of Ancash, across the Cordillera Blanca from Huaraz. The 13 meter-tall "new temple," with inward-sloping walls studded with carved heads, was completed around 800 B.C. The smaller "old temple," located above the circular plaza, was built around 1200 B.C., and contains in a subterranean gallery the heart of the temple, the enigmatic Lanzon.

The heart of the Chavin culture is the ceremonial center of Chavin de Huantar, a granite temple located in the northern mountains of Ancash, across the Cordillera Blanca from Huaraz. The 13 meter-tall "new temple," with inward-sloping walls studded with carved heads, was completed around 800 B.C. The smaller "old temple," located above the circular plaza, was built around 1200 B.C., and contains in a subterranean gallery the heart of the temple, the enigmatic Lanzon.In this photograph you can see the New Temple with the Square Plaza below it. The black and white stairs lead from the square plaza through the platform on which both temples rest, to the temple gate. The old temple is to the right of the new temple, and recessed. In front of it, but not visible in this photograph, is the circular plaza. The plaza, temple walls, and stairs are all original. The gate was restored to its original position by archeologists who found that it had collapsed.

The site was partially buried in 1945 by a landslide from the surrounding mountains, which destroyed the original bridge across the river to the temple, still in use after 3000 years.

The Square Plaza

The Square Plaza was apparently designed for outdoor ceremonies, possibly including feasts at festivals. It is surrounded by bleachers, which look like staircases to nowhere. The plaza is aligned so that when you stand in the center, the walls are located at the points of the compass. The front of the new temple faces due east, as does one wall of the plaza.

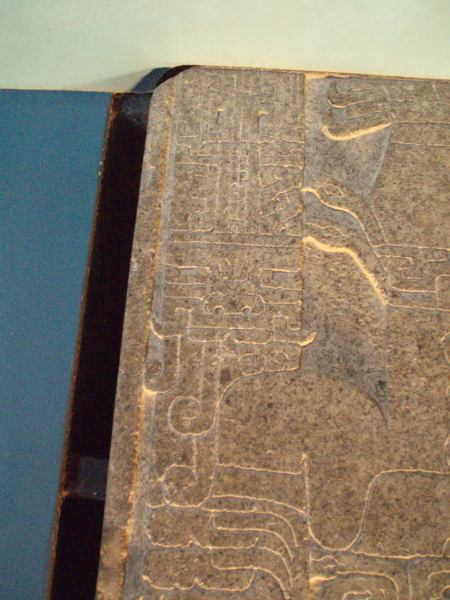

The interior wall of the sunken plaza was lined with fine stone panels. Many of the original panels were likely carved with religious images in the classic Chavin style. They probably resembled the below panels on display in the nearby museum.

The Altar and the Stela

As you ascend the stairs from the square plaza to the New Temple, you can see a carved limestone altar, with several bowl-shaped depressions. The depressions are thought to have been filled with water, perhaps to reflect the stars for ceremonial or astronomical purposes, as similar Inca structures were apparently used. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the altar is the rectangular shelf carved into the end facing the plaza. It is exactly the right size and shape to hold the Stela Raimondi, perhaps the most important single piece of Chavin art still in existance.

This is the Stela Raimondi, on display in a Lima Museum, and it is worth a closer look. This intricate granite slab was apparently removed from Chavin de Huantar by a farmer who wanted to use it as a table, but ultimately came to no harm.

This is the Stela Raimondi, on display in a Lima Museum, and it is worth a closer look. This intricate granite slab was apparently removed from Chavin de Huantar by a farmer who wanted to use it as a table, but ultimately came to no harm.The entire stela is a portrait of the "staff god," later worshipped by the Wari and Tiwanaku cultures as the creator of the universe. The bottom half of the stela is the deity himself, while the remainder comprises his headdress.

The Staff God, as portrayed here, has a fanged mouth and prominent nostrils, commonly thought to represent "feline" features. He grasps the two intricate staffs in clawed hands, and his feet resemble an eagle's talons. Adding to the mystery of his bizarre appearance is the fact that he is apparently not alone. If you look at the Stela upside-down, a series of dragon-like visages comes into view. The first two are at the base of each staff. The remainder are stacked up in the center of the headdress, with the most elaborate sharing the Staff God's eyes. Directly above that dragon is another face that appears exceptionally friendly; actually, several of these inverted faces seem to be smiling, in sharp contrast to the deity's fierce glare.

This last view of the inverted faces also affords an opportunity to see the snake heads on the ends of the Staff God's "hair."

This last view of the inverted faces also affords an opportunity to see the snake heads on the ends of the Staff God's "hair."All these inverted faces beg the question: did people ever view the Stela in an upside-down position? Was it held in a verticle position on the altar, as appears to be the case, or was that farmer ironically right in laying it flat like a table, so that it could be viewed from both ends?

The New Temple

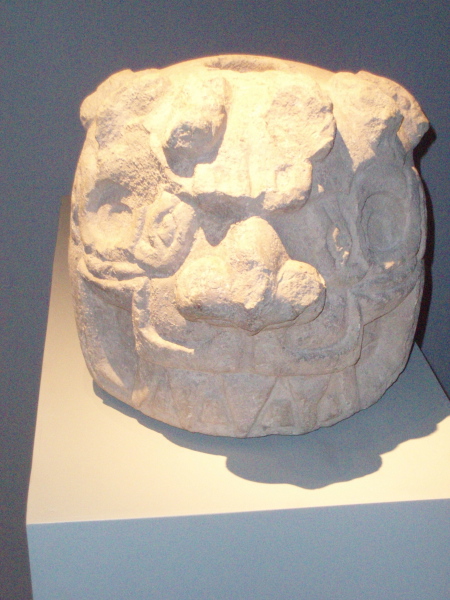

The New Temple, completed around 800 B.C., is a 13 meter tall structure with a rectangular base, and with walls that angle inward as they ascend, sometimes referred to as a "truncated pyramid." The walls were originally topped with a protruding cornice, and decorated with carved stone heads. Only one such head still remains on the rear wall of the temple, but the slots in which the heads were originally inserted are still visible on the walls, and several of the heads are collected in the nearby museum.

At the front of the New Temple is its main gate, which was restored by archeologists when it was discovered, collapsed, at its original location. The stairway from the Square Plaza ascends to the main gate and continues through it up to the top of the New Temple. The left-hand post of the gate is carved with a female character, as demonstrated by the V-shaped image between its legs, which is a stylized imitation of the female reproductive organs. On the right post is a male character, which has a little inverted triangle to represent the male reproductive organs. The lintel is also carved, though the images are faint. The left half of the lintel is white granite, and the right half is black limestone, matching the white granite panels along the wall on the left and the black limestone panels on the right. The stairway from the plaza through the gate is also black on the right and white on the left. It is only one of the stairways leading to the top of the temple; it is not open to the public, but other stairways are.

At the front of the New Temple is its main gate, which was restored by archeologists when it was discovered, collapsed, at its original location. The stairway from the Square Plaza ascends to the main gate and continues through it up to the top of the New Temple. The left-hand post of the gate is carved with a female character, as demonstrated by the V-shaped image between its legs, which is a stylized imitation of the female reproductive organs. On the right post is a male character, which has a little inverted triangle to represent the male reproductive organs. The lintel is also carved, though the images are faint. The left half of the lintel is white granite, and the right half is black limestone, matching the white granite panels along the wall on the left and the black limestone panels on the right. The stairway from the plaza through the gate is also black on the right and white on the left. It is only one of the stairways leading to the top of the temple; it is not open to the public, but other stairways are.

The New Temple Galleries

On the top of the New Temple are a few stairways that lead down into the galleries within the structure. These stairways are all original Chavin constructions, as are the galleries. The galleries' original use is, with one notable Old Temple exception, a matter of educated speculation. More recently, however, they were used by local farmers, who called the New Temple "El Castillo," to keep animals. When the first archeologists began investigating the site, the government excluded farmers from using the temple as a livestock barn, and from taking irreplaceable antiquities for use as tables or parts of stone walls. The farmers' respect for their culture appears to live on in the modern tourist, however; the curators have found it necessary to put signs up at each entrance admonishing tourists not to urinate in the galleries.

I wonder if they have that problem in the Vatican?

The first gallery shown here is the Gallery of the Double Cantilever, so called because there are two layers of stones that jut out from the wall to support the ceiling, rather than one. This gallery is also notable because it has the clearest remaining snake carving on one of its blocks. Other parts of Chavin have similar carvings on stairs and so forth that are much more badly faded.

The photo on the left shows the opening of a shaft on the gallery. There are many such shafts. They communicate between parts of galleries or between different galleries, and some go straight through the New Temple to the outside. At different times of year, the sunlight comes right through a shaft to illuminate a gallery. The shafts that have sunlight and air coming in demonstrate that at least some galleries in the New Temple are inside the structure, as opposed to underneath it--hallways, not tunnels.

The photo on the left shows the opening of a shaft on the gallery. There are many such shafts. They communicate between parts of galleries or between different galleries, and some go straight through the New Temple to the outside. At different times of year, the sunlight comes right through a shaft to illuminate a gallery. The shafts that have sunlight and air coming in demonstrate that at least some galleries in the New Temple are inside the structure, as opposed to underneath it--hallways, not tunnels.If you take a left at the Doble Mensula stairs you can enter the Gallery of the Columns, which has no electric lighting. These two photographs are illuminated almost exclusively by flash, but you can see the yellow disc of my little flashlight. In the second photograph, you can see one of the columns that give the gallery its name, on the right. It is made up of a bunch of small stones in mortar.

Note the sunlight coming in through the shaft in the second photograph. It looks like a window to the outside, but actually the outside is some distance away down the shaft.

The photograph on the left shows the stairway to the entrance of the gallery, and also a good look at the ceiling of the hallway. Ceilings and roofs are in short supply in Peruvian ruins. Many of the Inca buildings appear to have been thatched, and needless to say not repaired in the last 500 years, and the rest were torn down by the Spanish. Constructions from other cultures have had even longer to lose whatever once capped them. Chavin's deeply-set hallways have kept their ceilings, now supported by wooden braces for the sake of safety. As you can see, the ceiling tiles of choice were massive stones laid across the tops of the walls. For some reason, the ceiling of this gallery slants a bit, as if it was in an attic

The photograph on the left shows the stairway to the entrance of the gallery, and also a good look at the ceiling of the hallway. Ceilings and roofs are in short supply in Peruvian ruins. Many of the Inca buildings appear to have been thatched, and needless to say not repaired in the last 500 years, and the rest were torn down by the Spanish. Constructions from other cultures have had even longer to lose whatever once capped them. Chavin's deeply-set hallways have kept their ceilings, now supported by wooden braces for the sake of safety. As you can see, the ceiling tiles of choice were massive stones laid across the tops of the walls. For some reason, the ceiling of this gallery slants a bit, as if it was in an atticOne of the doorways off the entrance hallway of the Gallery of the Captives opens on stairs leading down to another gallery, closed to the public. We were able to enter five galleries altogether in the Old and New temple, but there are twenty-six galleries altogether. The entire network of tunnels and hallways is immense.

The Circular Plaza

To the right of the New Temple, as seen from the front, is the Circular Plaza, with the Old Temple behind it. The Circular Plaza is sunk much deeper for its width than the Square Plaza. It is lined with flat stone panels and niches. It also is thought to have served a ceremonial purpose, although it is not ringed with bleachers. One archeologist theorized that the Tello Obelisk once stood in the center, making the whole plaza into a kind of massive sundial. The Tello Obelisk is shown here on display in Lima's Archeology Museum, encased in glass for protection from tourists. It has since been taken back to Ancash, where it is going to be displayed in the Chavin Museum along with all those heads. It is carved with a bunch of figures and symbols, and is worth a look.

The Old Temple

The first structure in Chavin de Huantar was the Old Temple. It is a much less imposing building than the New temple that towers beside it, but it is the heart of the ceremonial site. The Old Temple has a modest one-story front with a couple of doorways in it. They lead to some of a system of galleries in and under the temple, similar to the ones in the new temple. Three of the galleries converge on the Lanzon, which is the idol at the heart of the site, and a third leads over it. A separate gallery, the Gallery of the Laberynth, is thought to have housed pilgrims who came to visit the Lanzon.

If you look at the entrance to the Gallery of the Laberynth, below, you can see an early example of ancient Peruvian architecture. The lintel over the doorway is a thick granite slab that extends to the right and left of the doorway. You see this in almost any doorway made by the Inca, the Wari, or anybody else who was building with stone in the region. Solid doorways, later modified to be trapazoidal in shape, were an important element of anti-seismic architecture. Another anti-seismic technique is on the left door-frame, which also is a corner of the wall. While the rest of the wall alternates large rectangular or unshaped stones with smaller ones, giving the wall greater strength, the corner is made up entirely of large, rectangular stones. This heavy construction at the corners of buildings gives them greater stability during earthquakes. You can see it in the stronger Wari and Inca constructions as well.

If you look at the entrance to the Gallery of the Laberynth, below, you can see an early example of ancient Peruvian architecture. The lintel over the doorway is a thick granite slab that extends to the right and left of the doorway. You see this in almost any doorway made by the Inca, the Wari, or anybody else who was building with stone in the region. Solid doorways, later modified to be trapazoidal in shape, were an important element of anti-seismic architecture. Another anti-seismic technique is on the left door-frame, which also is a corner of the wall. While the rest of the wall alternates large rectangular or unshaped stones with smaller ones, giving the wall greater strength, the corner is made up entirely of large, rectangular stones. This heavy construction at the corners of buildings gives them greater stability during earthquakes. You can see it in the stronger Wari and Inca constructions as well.

The Lanzon Gallery

The Lanzon is a 4 meter carved granite pillar shaped like a giant dagger plunged into the ground inside the Old Temple. It is carved with an elaborate, fanged, smiling figure, thought to represent some kind of deity. at the top of its head, it narrows into a thin post of stone that protrudes up through a hole in the ceiling into a higher gallery. It is thought that the priests in the upper gallery would pour some form of "sacrificial" fluid, which could be water, chicha, or blood, on that post, and it would run down through the lines carved in the Lanzon, perhaps throwing its features into relief. Maybe it was used as part of a ceremony of divination. Maybe the Lanzon was an oracle. Practitioners of the Chavin religion took San Pedro, a kind of peyote from a local cactus. It is commmon knowledge that South American shamans use hallucinogens, including San Pedro, to induce visions in themselves and their patients for medical and psychiatric purposes, as well as for spiritual and temporal guidance. The Chavin are thought to have conceived some of the bizarre images in their carvings during sessions with San Pedro. The only thing I have seen in Peru that is even remotely similar to the Lanzon is the oracular idol of Pachacamac, so it isn't hard to imagine ancient leaders traveling the vast distances (over the Cordillera Blanca from the coast!) to Chavin de Huantar for prophecies and guidance the way ancient Greeks would travel to Delphi. One of the three galleries leading to the Lanzon is open to the public. It is an unearthly sight with its illumination, and it is amazing to consider that this unique carving hasn't moved an inch in 3,200 years. That is one advantage of worshipping a large irregular piece of rock weighing several tons and lodged in a network of narrow tunnels.